If you haven’t yet heard Buddy Rich berating his band on the tour bus, stay tuned below for an 11-minute treat..!

Jazz history is full of famous recordings. Studio albums. Live broadcasts. Bootlegs captured from the audience. But there is an entirely different kind of recording that has circulated among musicians for more than forty years: a cassette of drummer Buddy Rich shouting at his band between gigs.

Here’s What’s Coming…

These recordings, known today as “The Buddy Rich Tapes,” were never meant for public consumption. They were captured privately by pianist Lee Musiker during his time in Rich’s band in the early 1980s and slowly passed from one musician to another. They don’t feature Rich’s drumming. They feature his voice: furious, driven, and determined to push his musicians harder than they thought possible.

The tapes became a kind of underground document. Not a performance, but an insight into the psychology of a legendary bandleader.

How the tapes began circulating

In a March 2002 article in JazzTimes, journalist Bill Milkowski wrote about the first time he heard the tapes. According to Milkowski, his friend and fellow musician Robert Quine gave him a cassette in 1984. Quine had received it through his work with Lou Reed, who, Milkowski writes, had at one point given out copies as Christmas presents.

This was long before the internet. There was no way to upload a file, no forum where musicians could trade clips, and no social network amplifying a short soundbite into cultural mythology. If you found something remarkable, you copied it onto a physical cassette and handed it to someone you knew would appreciate it.

The tapes travelled through that network: band to band, bus to bus, rehearsal room to rehearsal room, until almost anyone working professionally in jazz had heard at least fragments.

Who Buddy Rich was on stage

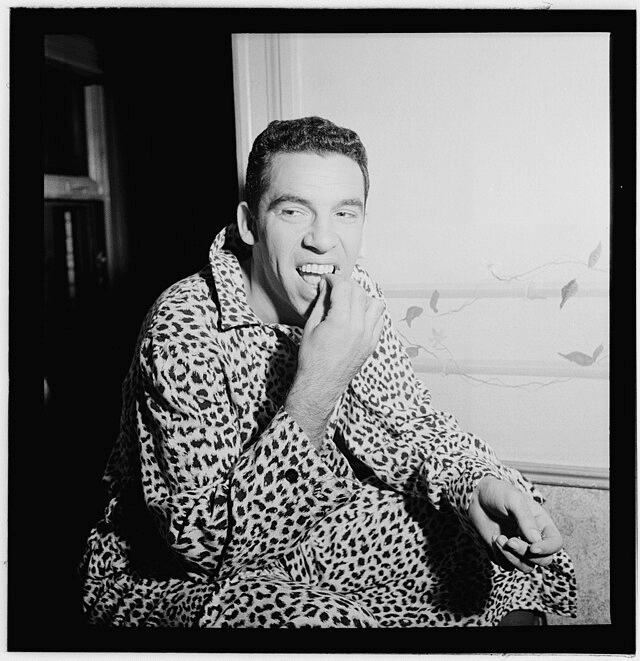

For many fans, Buddy Rich was the face of big band drumming in the television era. His appearances on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson made him a familiar figure even to non-jazz listeners.

On a commercial level, albums like Mercy, Mercy (1968) and Big Band Machine (1975) presented Rich as both a technical powerhouse and a showman. He was often described with superlatives: “the greatest drummer on the planet,” “lightning-fast hands,” “a genius of the kit.”

Rich was a confident performer who built an identity around extreme precision and control. Onstage, he projected authority and humour. Offstage, he carried the responsibility of running a touring big band in an era when the economics of such a group were increasingly difficult.

Those pressures form the context in which the tapes were made.

What the tapes actually contain

The tapes capture Buddy Rich speaking to his band after performances he considered substandard. The language is extremely strong. Rich’s tone is explosive. But the underlying theme repeats throughout the recordings: he felt the musicians were not matching his level of commitment.

One quote from the tapes has circulated more than any other. Addressing an argument about facial hair, Rich shouted: “Do you want a beard, or do you want a job?”

In another section, someone is told: “You’ve got two weeks to clean up your act if you want this job.” The speeches are often delivered as uninterrupted streams of reprimand and instruction, with a mixture of musical criticism and theatrical insult that is unlike anything else preserved from that period of jazz touring.

Milkowski describes the sound as “an imposing white-hot blast of verbiage,” noting that the intensity and musician’s slang immediately identify the voice. Rich’s criticism often focuses on ensemble roles, phrasing, accuracy, and the collective sound of the band. At times, he compares the musicians unfavourably with the great players he had worked with earlier in his career. The result is a kind of performance in its own right: not musical performance, but rhetorical performance.

Why Lee Musiker recorded them

The tapes exist because pianist Lee Musiker recorded them between January 1983 and January 1985. In Milkowski’s article, Musiker says he recorded the speeches out of a sense of history, and that he admired Rich as a musician and leader. Musiker describes Rich as someone who demanded “excellence and perfection” and expected everyone on stage to give their best effort.

Musiker states that the intent of the tapes was not to embarrass Rich. He used the same recorder to capture his own trio features on gigs so he could listen later and improve his playing. According to his account, the tapes circulated beyond his control when a fellow musician requested a copy before leaving to join another band. From there, they spread to players in other touring big bands, including those of Maynard Ferguson and Woody Herman, and eventually across the jazz community.

Leadership style and musical context

Many musicians who worked in large ensembles in the mid-twentieth century describe a leadership culture that was direct and demanding. Miles Davis was known for dismissing musicians without warning. Charles Mingus famously challenged players on stage. Count Basie and Duke Ellington maintained discipline through a more reserved authority, but their bands still operated with clear expectations and a deep sense of hierarchy.

Buddy Rich came out of that world. The bands he grew up watching or working within had very strong leaders. In that context, shouting at musicians was not uncommon, although very few leaders were recorded doing it. The tapes represent a rare document of a leadership style that would have been commonplace in certain eras of jazz touring. They show how standards were enforced and how musicians were encouraged—or pressured—to meet them.

A different interpretation of the tapes

For some listeners, the tapes are uncomfortable. They sound like verbal abuse directed at musicians doing their job. For others, particularly those who have spent time in high-pressure musical environments, the tapes sound like an extreme version of a familiar demand: unity of purpose, accuracy, and collective effort. Even the musicians involved did not always receive the speeches the same way.

Australian trombonist Dave Panichi, who features in one of the most widely quoted moments on the tapes, later commented that Rich respected him for not giving in easily. In interviews, Panichi suggested that cultural differences affected how the speech was received. He remained in Rich’s band for another year after the confrontation recorded on the tape.

That does not mean the tapes reflect best leadership practice, nor that they should be held up as a model. They reflect a specific time, a specific personality, and a specific tradition within jazz. They also show the stress of maintaining a large ensemble on the road in the final decades when a big band could still expect to tour internationally.

Listen: The Buddy Rich Bus Tape

The tapes survived because they are compelling in two ways. They are undeniably dramatic. But they also reveal something about the working conditions of a major jazz band. Behind the glamour of the stage and the charisma of the television appearances is a reality of travel, fatigue, high expectations, and a leader who believed that anything less than his best was unacceptable.

For historians, they offer a rare primary source for understanding how musicians communicated internally when they thought nobody else would ever hear it. For listeners, they raise questions about the relationship between artistic excellence and leadership style. The tapes have become part of jazz lore not only because they are intense, but because they present a complex figure in an unfiltered moment.

Below is one of the circulated recordings. It is not a musical performance. It is a moment between performances — a document of how one of the most famous drummers in jazz addressed his band.

Listening to the tapes today, one might ask what leadership means in music. In Rich’s world, the band existed as a single instrument. Every misplaced phrase weakened the whole. He expected absolute commitment because he gave it himself every night. Whether that justified the method is another question. The tapes present the tension between ambition and humanity in its rawest form.

Looking for more Buddy? Check out our pick of his essential recordings, or a recap of Buddy Rich’s greatest albums.