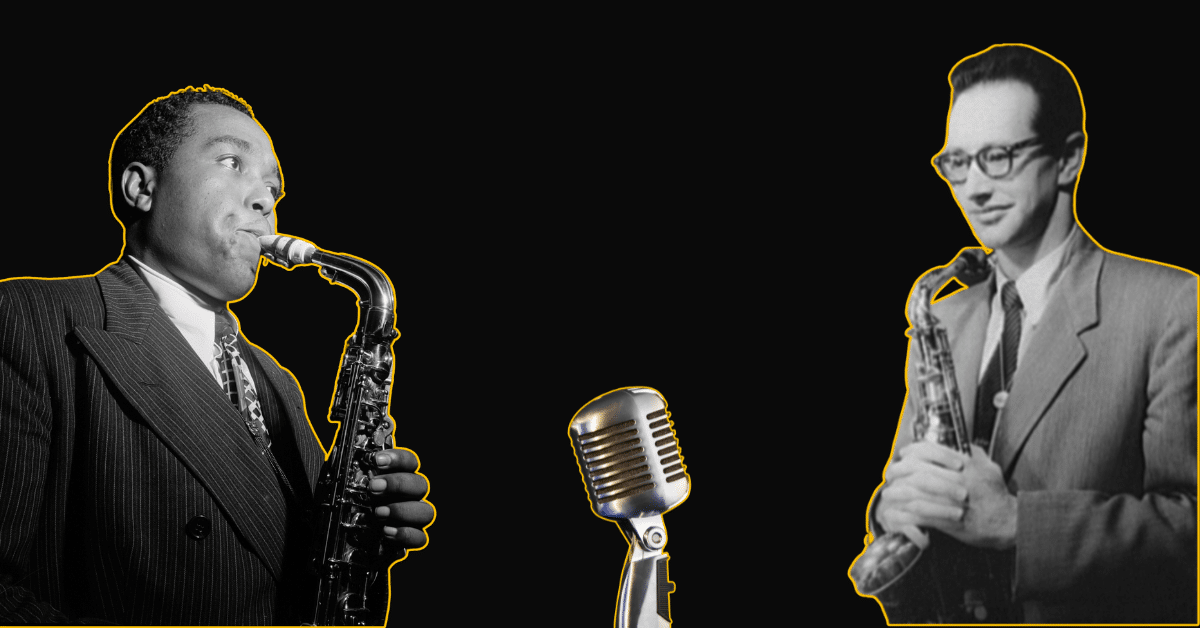

For all the stories and mythologies surrounding Charlie Parker — the saxophone prodigy, the bebop pioneer, the tragic genius — few moments bring us as close to the man himself as this rare recorded interview with fellow alto great Paul Desmond.

Filmed in the 1950s, it’s an unusually candid and humble window into Parker’s philosophy: his thoughts on sound, storytelling, technique, and the responsibility of musicianship.

What’s most striking, though, is how little ego comes through — even when Desmond, visibly awestruck, describes Parker’s impact in terms of “changing the entire scene.”

Parker shrugs that off.

“No, I had no idea it was that much different,” he says, referring to the revolutionary sound of his early records. “That was my first conception, man. That’s the way I thought it should go.”

Parker’s style — explosive, articulate, harmonically advanced — didn’t emerge from thin air. It came from a deeply internal vision of how music could be both precise and poetic, deeply felt yet technically stunning.

“Ever since I ever heard music, I thought it should be very clean, very precise… and more or less to the people. Something they could understand. Something that was beautiful.”

This sense of emotional responsibility — of music being for someone, not just about something — is echoed again and again. For Parker, the alto sax was not a tool of self-indulgence but a channel for stories: emotional, human, and expressive beyond words.

“There are stories and stories and stories that can be told in the musical idiom… Music is basically melody, harmony and rhythm. But people can do much more with music than that.”

Desmond, clearly reverent, tries to pin Parker down on a more technical question: Where did his famously lightning-fast technique come from? Was it raw talent? Or practice?

Parker’s answer is both modest and deeply revealing.

“I can’t see where there’s anything fantastic about it at all. I put quite a bit of study into the horn, that’s true.”

He pauses, then drops a line that’s become near-legendary among musicians:

“The neighbours threatened to ask my mother to move once… I was driving them crazy with the horn. I used to put in at least 11 to 15 hours a day. I did that over a period of 3 or 4 years.”

That work ethic — not just talent — is what made Parker great. And he knew it. Even in an era where jazz musicians were often mythologised as hard-living natural geniuses, Parker wanted to set the record straight.

“Study is absolutely necessary in all forms. It’s just like any talent that’s born within somebody — it’s like a good pair of shoes when you put a shine on it.”

The analogy is simple, but the sentiment is clear: genius is nothing without discipline.

He even invokes Einstein as an example — a man with both innate brilliance and the humility to undergo rigorous education.

“Einstein had schooling, but he had a definite genius within himself. Schooling is one of the most wonderful things there has ever been.”

There’s something deeply refreshing about hearing Parker — a man who by then had already changed the course of jazz — speak so passionately about work. And not just the glamorous parts, but the hours and years spent alone with his instrument, his books, and his sound.

It’s a rare reminder that behind even the most spontaneous art is often a lifetime of deliberate preparation.

Watch the full video here and hear Bird in his own words:

Looking to dig deeper into the world of Charlie Parker? Here’s the story of his early years.