Jazz history is full of unexpected pairings, but few are as intriguing as the moment Cannonball Adderley decided to record an entire album of music from Fiddler on the Roof.

At first glance, a musical set in Imperial Russia and the soulful, gospel-infused sound of Cannonball’s sextet seem like strange bedfellows. But the resulting 1964 album — released on Capitol and arranged by the young Joe Zawinul — became one of the most inventive interpretations of musical theatre in jazz.

And behind the scenes, according to producer David Axelrod, the session ended with Cannonball firing his tenor player, Charles Lloyd, only moments after the final take.

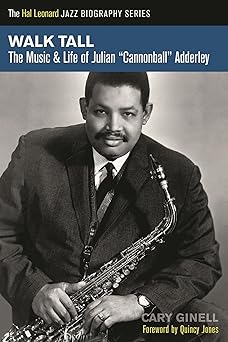

The story, told in Cary Ginell’s meticulously researched biography Walk Tall: The Music and Life of Julian “Cannonball” Adderley gives a rare glimpse into how Cannonball viewed band chemistry, artistic direction, and the delicate balance between personality and discipline that defined his group.

This is the story of how the album came to be, why the music works far better than anyone expected, and what really happened in the studio that day.

A Broadway Hit Meets a Working Band

The early 1960s were a period of expansion for Cannonball’s sextet. The band — featuring Nat Adderley on cornet, Joe Zawinul on piano, Sam Jones on bass, Louis Hayes on drums, and (for a period) Yusef Lateef on woodwinds — was one of the hardest working small groups in jazz. Their mix of blues, soul, hard bop, and accessible melodies made them audience favourites.

By 1964, Lateef had left to form his own group. Cannonball replaced him with a rising talent: Charles Lloyd, who could play both tenor saxophone and flute and had an emerging reputation for pushing musical boundaries.

Around this time, Cannonball and his longtime producer David Axelrod were looking for a fresh concept — something that could reach beyond the typical jazz repertoire without feeling gimmicky.

The Broadway production of Fiddler on the Roof had just premiered and was already a sensation. The combination of strong melodies, minor-key themes, folk influence, and emotional range appealed to both Cannonball and Axelrod.

According to Axelrod, the idea seemed almost too perfect:

“It had everything! Harmonic minor scales, Jewish melodies, jazz possibilities — it couldn’t miss.”

Capitol Records agreed to the project, and the band went into the studio in New York.

Why the Music Works

The strength of the album lies in its treatment of the source material. Rather than parodying or smoothing out the Broadway flavour, Cannonball and Zawinul leaned into what made the songs distinctive.

Joe Zawinul’s Arrangements

Zawinul was only in his early 30s, but he was already experimenting with voicings, rhythms, and textures that foreshadowed his later work with Weather Report. His arrangements respected Jerry Bock’s original melodies while opening up space for improvisation.

“Tradition,” for example, becomes a driving minor-key groove. “Fiddler on the Roof” turns into a modal platform, with Cannonball’s alto riding over Zawinul’s rhythmic vamp. “To Life” shifts between moods with quick, sharp energy that suited the sextet perfectly.

Cannonball’s Voice

Cannonball always had the ability to take unfamiliar material and make it feel deeply personal. On this album, he brings a mix of blues phrasing, bebop fluency, and sheer optimism that lifts the songs beyond their theatrical origins.

These aren’t Broadway covers. They’re Cannonball Adderley performances — warm, soulful, and incisively musical.

A Band in Transition

The sextet was in the midst of personnel changes, but the playing is tight, focused, and joyful. Lloyd’s presence brings a slightly more searching, modern edge, while Nat Adderley’s cornet provides balance, grounding the material in gospel and blues.

“You’re Fired. You’re Through. Get Out of Here!”

Despite the strong performances, the session ended with drama.

According to David Axelrod’s account in Walk Tall, the final minutes of the recording included a moment Cannonball found impossible to let pass.

Axelrod recalls that Cannonball had specifically encouraged Charles Lloyd not to imitate John Coltrane during solos — not because he disliked Coltrane, but because he wanted Lloyd to bring his own voice rather than chase a trend.

“Just play,” Cannonball told him.

But during the session, Lloyd slipped into long, cascading sheets of notes — what Axelrod called “a thousand notes in every bar.” When the group finished their last take, Cannonball turned to Lloyd and said:

“You’re fired. You’re through. Get out of here.”

Axelrod remembered Lloyd looking embarrassed and Cannonball visibly frustrated. It wasn’t personal — Cannonball was famous for being kind and generous — but he was deeply protective of his band’s musical identity.

Lloyd, of course, went on to a remarkable career of his own, forming his groundbreaking 1966 quartet with Keith Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette. But his short stay in the Adderley sextet ended right there, in the studio, moments after the final track of Fiddler was wrapped.

Legacy of Fiddler on The Roof

Fiddler on the Roof remains one of Cannonball Adderley’s most fascinating projects:

- It captures a band at a crossroads.

- It showcases Zawinul’s budding genius.

- It shows Cannonball’s willingness to take risks with repertoire while demanding discipline in execution.

- And, thanks to Axelrod’s eyewitness account, it offers one of the most memorable behind-the-scenes moments in Cannonball’s career.

The album didn’t become a major hit, but it stands as a testament to a working band stretching its boundaries — and to Cannonball’s firm belief that jazz, even when playful, required honesty, individuality, and commitment.