Search for Warne Marsh albums and you quickly notice something odd.

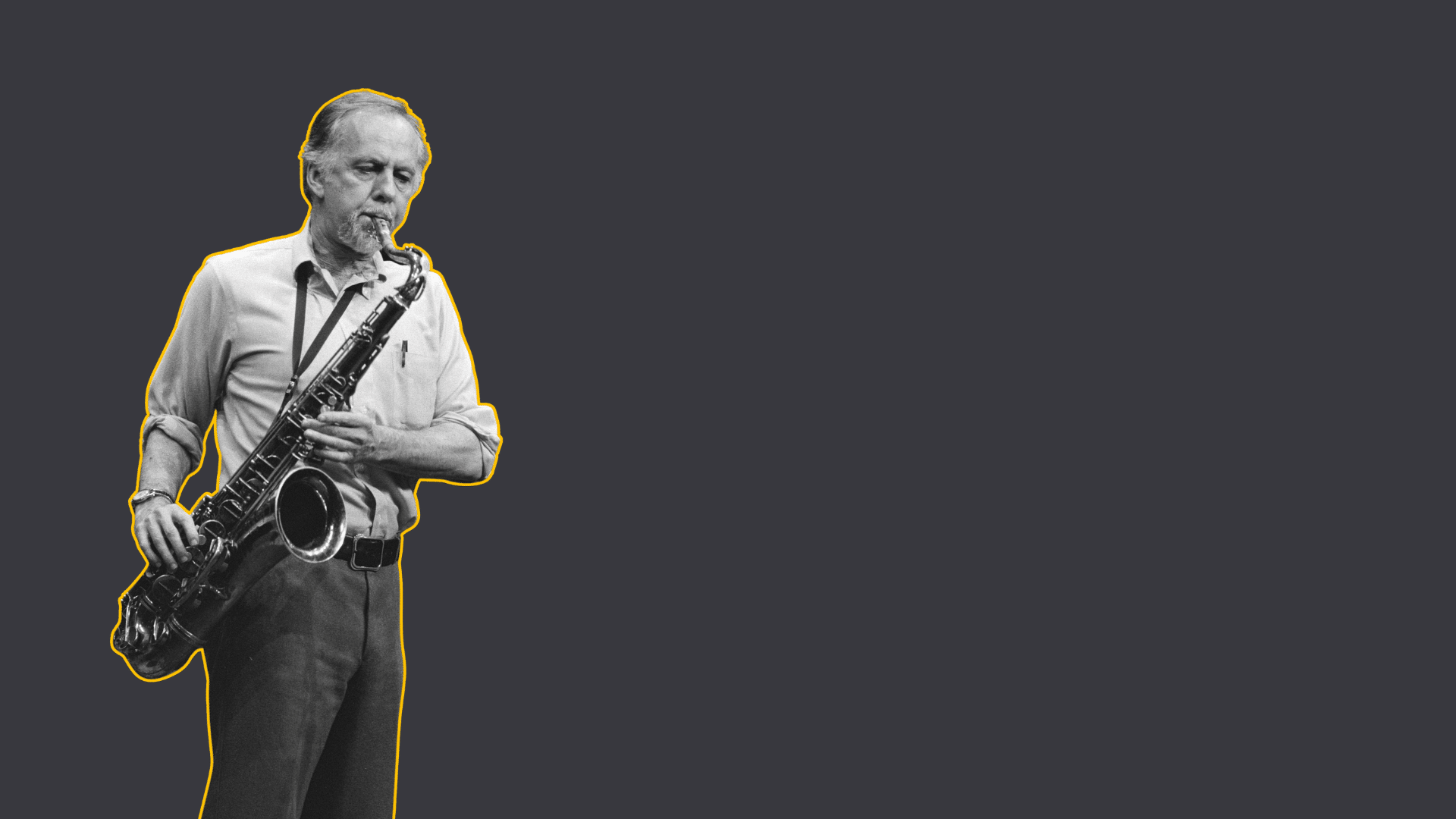

Here is a saxophonist who shaped generations of improvisers, earned the respect of some of the sharpest minds in jazz, and sustained a devoted following over six decades — yet never became a household name in the way many of his peers did.

Some of that is historical. Some of it is personality. And some of it lies in the music itself.

Warne Marsh never tried to sell an image. He didn’t cultivate drama, chase trends, or wrap his playing in easy emotional narratives. What mattered to him was how melodies behave over harmony — how lines unfold, connect, and resolve over time.

Listening to Marsh is less like watching fireworks and more like watching a great chess player think several moves ahead.

This guide isn’t a list of “best records.” It’s a way into his world — a path through the albums that explain not just what he played, but how and why he played it that way.

The Tristano Connection: Where It Starts

To understand Warne Marsh on record, you have to begin with his musical upbringing.

In the late 1940s, Marsh became part of the circle around pianist and teacher Lennie Tristano, alongside Lee Konitz. This wasn’t a scene so much as a shared way of thinking: deep study of harmony and counterpoint, intense rhythmic discipline, and a belief that improvisation should be both spontaneous and structurally sound.

The most famous document of that partnership is Lee Konitz with Warne Marsh (1955).

This is often the best place to start — not because it’s flashy, but because it shows Marsh in his natural environment. Two horns move independently yet in sympathy, outlining harmony through long, interlocking lines. Nothing is forced. Nothing is overstated.

Spend time with this record and Marsh’s core language becomes clear: extended melodic arcs, subtle rhythmic displacement, and an uncanny sense of where the harmony is headed before it arrives.

If you’ve ever wondered what musicians mean when they talk about “line,” this album answers the question without explanation.

Becoming a Leader: Jazz of Two Cities

By the mid‑1950s, Marsh was ready to step forward on his own terms.

That happens most clearly on Jazz of Two Cities, recorded in Los Angeles in 1956. Paired with fellow tenor Ted Brown, Marsh treats each tune like a working sketch — themes stated plainly, then bent, tested, and reshaped through improvisation.

What’s striking is how little West Coast cliché you hear. The sound may be light and transparent, but the music has real urgency. Marsh isn’t floating. He’s driving.

This is the moment where he stops sounding like part of a movement and starts sounding like a bandleader with a clear internal compass. If the Konitz record teaches you the language, Jazz of Two Cities shows Marsh writing his own sentences.

Standards, Clarity, Control: Music for Prancing

For many listeners, the most welcoming doorway into Marsh’s music comes through familiar material.

That’s where Music for Prancing (1957) excels.

Recorded with Ronnie Ball, Red Mitchell, and Stan Levey, the album mixes standards with originals and lets Marsh demonstrate how much character he can bring to well‑worn tunes without raising his voice. Ballads unfold patiently. Faster numbers stay relaxed but razor‑sharp.

What makes this record special is how much personality emerges without any grand gestures. Marsh trusts the harmony to carry emotional weight. He shapes melodies with small inflections rather than dramatic emphasis.

Listen closely and you hear constant decision‑making — tiny rhythmic shifts, quiet re‑routes through the changes. This is precision without stiffness, intellect without distance.

A Major‑Label Snapshot: Warne Marsh (Atlantic)

In 1958, Marsh recorded his most prominent major‑label session as a leader.

The Atlantic album Warne Marsh places him alongside heavyweight rhythm players, including Paul Chambers and Paul Motian, with Philly Joe Jones appearing on select tracks. The result is a slightly heavier feel than the West Coast dates — more gravity, more muscle in the swing.

What’s fascinating is how easily Marsh adapts.

His language doesn’t change, but his phrasing tightens. He digs in rhythmically without ever sounding aggressive. Rather than imposing himself on the band, he integrates seamlessly.

If you want to hear Marsh in a classic, no‑nonsense jazz album setting, this is as close as it gets.

The Long Middle Years — and a Quiet Renaissance

After the 1950s, Marsh’s discography becomes less straightforward.

He worked constantly, taught, toured, and remained deeply respected, but without a steady presence on major labels. As a result, many listeners assume his prime ended early.

That assumption doesn’t survive contact with All Music.

Recorded in 1976, this album captures Marsh in a state of renewal. The lines are still precise, but looser now — more playful, more expansive. Backed by Lou Levy, Fred Atwood, and Jake Hanna, he sounds liberated rather than reflective.

The repertoire says it all. Marsh plays his own music alongside compositions by Tristano and Konitz, acknowledging his roots while showing how far he’s travelled.

This isn’t nostalgia. It’s growth.

For many listeners, All Music is the album that rewrites the entire narrative.

Long‑Form Freedom: Ne Plus Ultra

Around the same time, Marsh began recording more extended, exploratory sessions.

Ne Plus Ultra (1975) captures him in long‑form improvisational flight. Here, the lines seem endless, the harmony navigated at speed, the improvisation unfolding like thought made audible.

By this stage, Marsh sounds utterly unselfconscious. There’s nothing left to prove. He simply plays.

This late‑period freedom is one reason so many modern saxophonists hold him in such high regard. The music points forward without abandoning tonal clarity — a rare balance.

Old Partnerships, New Contexts: Crosscurrents

Recorded in 1977, Crosscurrents reunites Marsh and Konitz in the harmonic world of Bill Evans.

Though officially an Evans album, it functions as a conversation between long‑time musical allies. The pacing is elastic, the lines more lyrical, the interaction subtle and deep.

It’s a reminder that Marsh’s concept was never rigid. He could adapt to different harmonic philosophies without losing his identity.

Nowhere to Hide: Warne Out

If you want Marsh with no safety net, listen to Warne Out.

This stripped‑down trio session places everything in the open. Every line has to imply the harmony. Every rhythmic choice matters.

What emerges is not severity, but wit. Marsh sounds relaxed, occasionally mischievous, and deeply confident — the sound of a master enjoying his craft.

Two Tenors, Turned Up: Apogee

One of the more unexpected entries in Marsh’s catalogue is Apogee, co‑led with Pete Christlieb.

It’s high‑energy, front‑line music — not the context most people associate with Marsh — yet he fits perfectly. His lines cut through the intensity without becoming forceful. He meets fire with intelligence.

Put him anywhere, and his language holds.

How to Listen

If you’re new to Warne Marsh, think in stages.

Start with Lee Konitz with Warne Marsh. Learn the language.

Move to Jazz of Two Cities and Music for Prancing. Hear him lead and interpret.

Jump to All Music. Discover the late flowering.

From there, explore outward.

What you’ll hear isn’t reinvention, but refinement — a lifetime spent clarifying an idea.

Why Warne Marsh Still Matters

In a music culture that often rewards spectacle, Warne Marsh represents something quieter and more durable.

He shows that depth doesn’t need volume. That influence doesn’t require promotion. That a lifetime of serious work can speak for itself — if listeners are willing to meet it halfway.

Listening to his albums feels like reading a thinker’s notebooks over fifty years. Ideas emerge, evolve, collide, and mature. The rewards come slowly, but they last.

Final Thoughts

If you’re searching for a single “definitive” Warne Marsh album, you won’t find one.

What you’ll find instead is a body of work that reveals itself over time.

Start anywhere. Listen closely. Let the lines unfold.

That’s how Warne Marsh intended it.