“To Be Young, Gifted and Black” is often described as an anthem. And it is. But that word can flatten what the song actually is — and where it came from. Stay tuned for a deeper dive into the story behind the song, as well as an interview and performance by Nina Simone.

Before it became a statement of pride, it was a response to loss.

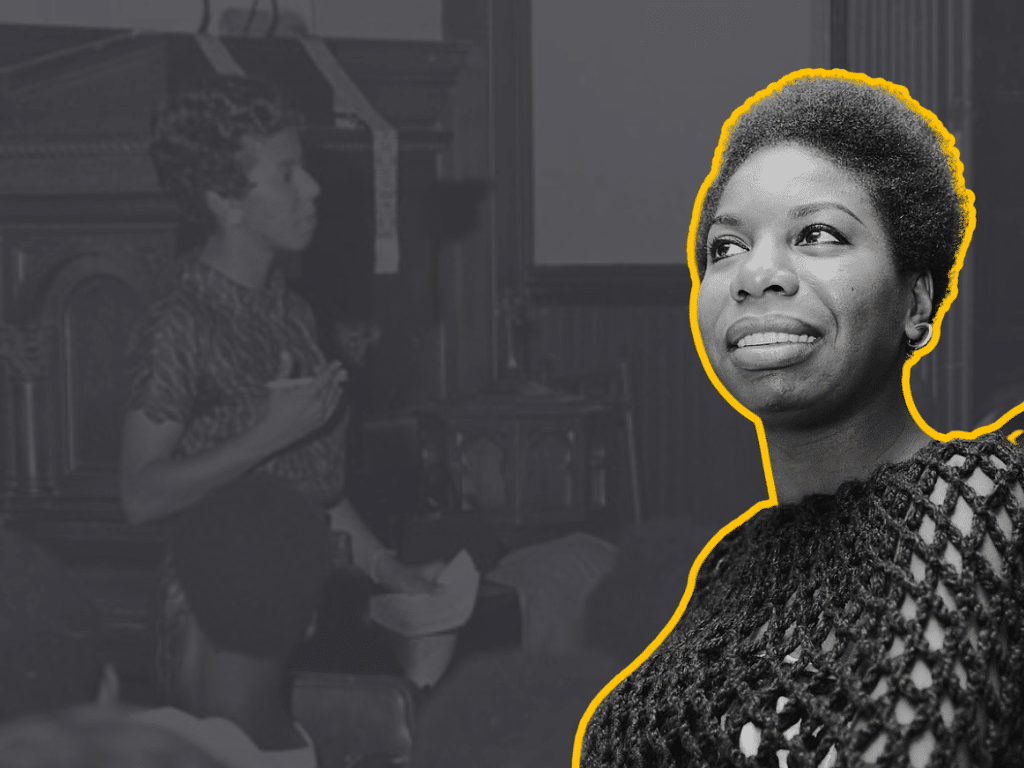

The person at the centre of that loss was Lorraine Hansberry, the playwright best known for A Raisin in the Sun.

Hansberry and Nina Simone met in the early 1960s and quickly recognised something in one another. They were both sharp, uncompromising, and impatient with shallow thinking. They talked constantly — about race, politics, responsibility, and the limits placed on Black artists in America.

Hansberry, in particular, pushed Simone to think more clearly about what she was already feeling. She encouraged her to read more, to speak more directly, and to stop softening her instincts to make others comfortable. Simone later said that Hansberry helped her understand herself as a Black woman living inside a historical moment, not just as a musician reacting emotionally to events.

In short, Hansberry mattered.

Then, in 1965, she died of pancreatic cancer. She was just 34 years old.

The death shocked Simone. Friends later described her as devastated — not only by the loss itself, but by how sudden it was. Hansberry had seemed essential, permanent. Someone you argued with, leaned on, sharpened yourself against. And then she was gone.

Simone struggled to process it.

A phrase that stayed behind

Before her death, Hansberry had been working on a new play. She never finished it, but she left behind a title she cared deeply about:

To Be Young, Gifted and Black.

It wasn’t a slogan. It was an assertion. A refusal to accept the way Black life was usually described in American culture — especially Black youth, who were so often framed in terms of deficiency or danger.

After Hansberry’s death, Simone returned to the phrase. At first, she didn’t write a song as such. Instead, she composed a tribute piece called “Young, Gifted and Black,” which explicitly referenced Hansberry by name. It was personal, almost private — closer to a eulogy than a pop song.

But Simone realised the phrase could do more than mark her grief.

By the late 1960s, the political climate had shifted sharply. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X were dead. The civil rights movement was fragmenting. Young Black Americans were being told, in a thousand different ways, that their futures were limited.

Simone understood that Hansberry’s words could speak directly to that moment.

To help shape the piece into something that could travel, she worked with Weldon Irvine, a young writer and musician. Together, they transformed it into “To Be Young, Gifted and Black.”

Not a protest song — something else

The song first appeared in 1969, on Simone’s live album Black Gold. It wasn’t written with radio in mind. There’s no flashy hook, no attempt to soften the message.

Instead, Simone delivers the song carefully, almost deliberately. She sounds like someone addressing an audience she takes seriously — not performing at them, but speaking to them.

“To be young, gifted and black

Oh what a lovely precious dream…”

The power of the song is in its refusal to argue. Simone doesn’t ask permission. She doesn’t debate. She simply states that Blackness, youth, and giftedness can — and do — exist together.

At a time when Black identity was often framed through pain or struggle alone, that mattered.

From tribute to inheritance

Although the song began as a response to one specific loss, it didn’t stay there.

Other artists quickly recognised what Simone had created. Aretha Franklin recorded her own version, bringing the song into a gospel- and soul-inflected space. Donny Hathaway recorded it too, and it became a fixture in schools, churches, and community halls.

In those settings, many listeners didn’t know about Hansberry at all. They didn’t need to.

The song had detached itself from its origin and become something people could claim for themselves — a kind of inheritance passed forward rather than a memorial looking back.

That, arguably, is what Hansberry would have wanted.