Some jazz singers are remembered for their voices.

Others for the songs they popularised.

A smaller group are remembered for personality alone.

Mel Tormé belongs to a rarer category: musicians who brought all three together — and sustained that balance across an entire career.

Mention his name and many listeners still think first of the nickname “The Velvet Fog”, or of his effortless technique. What tends to get lost is how deliberately he shaped his recorded output, and how seriously he approached the album as a musical statement rather than a loose collection of performances.

Spend real time with his catalogue and the polish gives way to something deeper.

What emerges is a musician who thought carefully about repertoire, phrasing, harmony, tempo, and context — someone intent on making records that would endure, not merely charm on first contact.

This guide looks at key Mel Tormé albums as part of a continuous artistic life, tracing his development from precocious entertainer to one of jazz’s most complete vocal stylists.

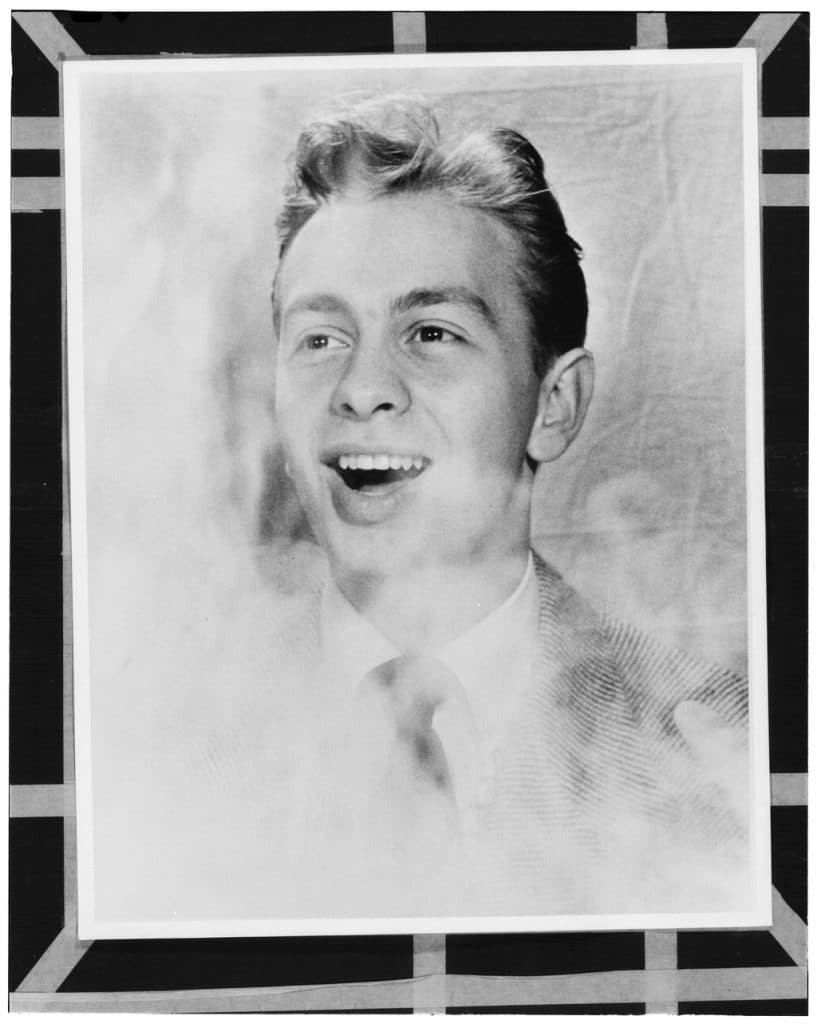

Growing Up in Public

Tormé’s early career unfolded in full view.

He appeared in films and radio as a teenager, worked in Hollywood as a songwriter, and became professionally active long before most musicians have worked out who they are. By his early twenties, he was already established as a singer, pianist, arranger, and composer.

That exposure had consequences.

On one hand, it gave him exceptional technical control. Microphones, studios, and audiences never felt foreign to him. On the other, it fixed him in many minds as a “show business” figure — a gifted entertainer rather than a serious jazz musician.

Tormé understood that tension.

Much of his later work can be read as a sustained attempt to prove that musical depth and accessibility did not have to be mutually exclusive.

His albums tell that story better than any biography.

The Turning Point: The Marty Paich Dek‑Tette

The clearest shift in Tormé’s recorded legacy comes in the mid‑1950s with his collaboration with arranger Marty Paich.

The Dek‑Tette recordings place Tormé in a refined small‑ensemble setting — neither big band nor combo — where arrangement and improvisation meet on equal terms. The first volume, recorded in 1956, remains one of his defining statements.

What makes these records work is balance.

Paich’s charts are intricate but never busy. They give Tormé room to move while surrounding him with harmonic and rhythmic detail. Tormé responds with relaxed phrasing, unforced swing, and a time feel that sits perfectly inside the band.

There is nothing performative about these records.

No one is “trying” to sound like a jazz musician.

This is a jazz singer operating naturally within a jazz environment.

For many musicians, these albums were the moment Tormé’s reputation quietly but decisively changed.

Swing Without Strain: Swingin’ on the Moon

Recorded in 1960, Swingin’ on the Moon shows just how comfortable Tormé was inside fast‑moving swing.

The tempos are brisk, the arrangements punchy, and the performances focused. What’s striking is how little effort you hear. Tormé never pushes against the band. He places phrases calmly inside the groove, trusting his internal clock and the ensemble’s momentum.

Even at speed, his diction stays clear. His tone remains centred. The swing never hardens.

This album does important corrective work. It reminds listeners that Tormé was not primarily a ballad specialist, but a deeply rhythmic singer with a secure relationship to time.

Judgement Over Gesture: Sings Fred Astaire

Tormé’s connection to the Great American Songbook was rooted in understanding rather than reverence, and Mel Tormé Sings Fred Astaire makes that clear.

Rather than treating Astaire’s repertoire as nostalgia, he approaches the songs as living material. He respects their shape while quietly rebalancing them through phrasing, harmonic awareness, and tempo choice.

What stands out is restraint.

There is no emotional overstatement, no exaggerated rubato. The melodies are allowed to do their work, supported by subtle inflection and precise timing.

This album captures something central to Tormé’s musicianship: his belief that interpretation is a matter of judgement, not decoration.

Intimacy and Control: It’s a Blue World

Some of Tormé’s most revealing work appears in smaller settings.

It’s a Blue World, recorded in 1962, places him in a restrained, intimate context that rewards nuance. The repertoire leans inward, and the performances emphasise tone, pacing, and harmonic awareness.

Tormé sounds thoughtful here — attentive to colour, careful with weight, unhurried in his delivery. He shapes lines patiently, letting phrases resolve naturally rather than pushing them toward effect.

There is nothing sentimental about this album.

Emotion arrives through proportion, not exaggeration.

The Live Musician: At the Crescendo

Tormé’s reputation as a studio craftsman sometimes overshadows his ability as a live performer. At the Crescendo, recorded in Los Angeles in 1957, corrects that.

This is a relaxed club date with high musical standards. What comes through most clearly is his command of pacing. He knows how to shape a set, how to vary mood and tempo, and how to engage an audience without turning performance into routine.

The band swings. The singing stays focused.

The atmosphere is warm, never casual.

It’s a reminder that precision and spontaneity were never opposing forces in Tormé’s work.

Renewal and Perspective: Live at the Maisonette

After a difficult stretch in the 1960s and early 1970s — marked by health issues and industry frustrations — Tormé experienced a genuine artistic revival.

Live at the Maisonette, recorded in New York in 1975, captures him at that moment.

The voice is strong. The phrasing is supple. The humour is present but never dominant. There’s a sense of ease that comes from no longer needing to prove anything.

This is late‑career confidence without complacency — a musician reconnecting with his strengths and trusting them fully.

Technique in Service of Music

Tormé’s technical equipment was extraordinary: wide range, secure intonation, exceptional breath control. What mattered was how he used it.

He rarely sang in a purely vocalistic way.

He thought like an instrumentalist.

His lines follow harmony. His phrasing mirrors horn players. His swing is grounded in time rather than gesture. He could sit behind the beat, lean into it, or float above it, depending on context.

Underlying everything was judgement.

Tormé valued clarity over display, balance over excess, and musical truth over dramatic effect. Those priorities shape all of his best recordings.

The Composer’s Mind

Although best known as a singer, Tormé’s background as a composer mattered deeply. Co‑writing “The Christmas Song” as a teenager was not an anomaly; it was a sign of how early he understood structure, melody, and form.

That compositional awareness informed his singing. He understood songs from the inside — how melodies function, how harmony supports narrative, how form shapes meaning.

It’s one reason his interpretations feel coherent rather than decorative.

Finding Your Way In

Approaching Mel Tormé’s catalogue works best through contrast:

- The Marty Paich Dek‑Tette recordings for modern jazz context

- Swingin’ on the Moon for rhythmic authority

- Sings Fred Astaire for interpretive intelligence

- It’s a Blue World for ballad control

- At the Crescendo for live command

- Live at the Maisonette for late‑career renewal

Together, they form a complete picture of a musician who kept refining rather than reinventing.

Why Mel Tormé Still Matters

Mel Tormé matters because he represents a model of vocal jazz built on musicianship rather than image.

He didn’t exaggerate emotion.

He didn’t trade depth for popularity.

He invested in craft, preparation, and long‑term development.

Over time, his albums stop feeling like individual projects and start to resemble chapters in a carefully constructed musical life.

From the sophistication of the Dek‑Tette sessions to the assurance of his later live work, the values remain consistent: rhythmic precision, respect for songs, and commitment to honest expression.

That consistency — quiet, deliberate, and deeply musical — is the foundation of Mel Tormé’s lasting place in jazz history.